As billions of U.S. dollars flowed in to rebuild Afghanistan following the fall of the Taliban in 2001, many contractors were accused of skimming reconstruction funds. Today, some of them own luxury properties in Dubai.

Key Findings

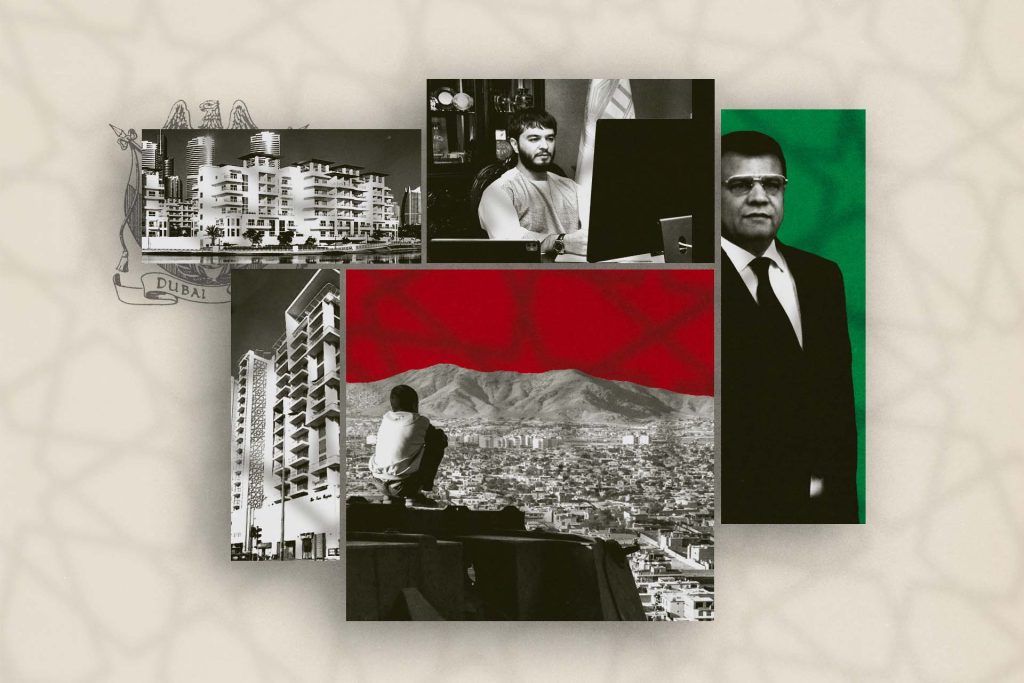

- Former Afghan parliament speaker Mir Rahman Rahmani and his son Ajmal spent more than $15 million on real estate in Dubai. In emailed responses to questions, the Rahmanis rejected U.S. allegations that they profited from a corrupt fuel supply contract.

- Their holdings include multiple apartments and villas, as well as two high-rise buildings that generate millions in rental income every year.

- Leaked data reveals at least three other contractors who were ensnared in scandals over U.S. procurement contracts in Afghanistan also own Dubai real estate.

The former speaker of Afghanistan’s parliament and his son, who were sanctioned late last year for allegedly misappropriating U.S. government aid, own luxury real estate in Dubai worth millions of dollars, property records reveal.

Mir Rahman Rahmani and his son Ajmal poured at least $15.2 million into properties in the glittering Gulf city, including two residential high-rise buildings and two large villas in The Meadows, an exclusive suburban community featuring tennis courts and swimming pools.

The revelation comes just months after the Rahmanis were slapped with U.S. Treasury Department sanctions alleging that they siphoned off millions of dollars in American reconstruction funds during the years between the fall of the Taliban in 2001 and their sweeping return 20 years later. (The Rahmanis challenged the sanctions in a lawsuit filed against the U.S. government on January 31.)

The former speaker of Afghanistan’s parliament, Mir Rahman Rahmani.

The sanctions notice, issued in December 2023, also blocked dozens of international companies it said Ajmal Rahmani owned or controlled as part of an “international corporate network.” The Treasury Department did not say where the Rahmanis had invested the profits of the contracting business. But an investigation by OCCRP, Lighthouse Reports, and Etilaat Roz found that they bought real estate in Dubai during and after the period the U.S. says they were allegedly engaged in corruption in Afghanistan.

At least two of the companies named by the U.S. were used to develop large residential complexes in Dubai, Ocean Residencia and Fern Heights, which contain a total of 228 units that generate over $2 million in rental income every year, according to rental contracts obtained by OCCRP.

In Germany, land registry documents show that six companies owned by Ajmal Rahmani hold real estate worth at least 197 million euros ($212 million), according to new reporting by an OCCRP partner, ZDF frontal. (In a written response to questions Ajmal Rahmani said he was “unable to confirm this figure.”)

In turning to Dubai, the Rahmanis were part of a larger trend. OCCRP and over 70 international partners collaborating as part of the Dubai Unlocked investigation have found the United Arab Emirates are a key destination for politicians, sanctioned people, and criminal figures from around the world.

The Gulf city is far from the only place where criminals and others have successfully stashed their wealth in luxury properties. New York City and London real estate have also been known to attract dirty money. But Dubai offers a particularly permissive climate for individuals looking to launder illicit cash via property purchases.

About the Dubai Unlocked Investigation

Dubai Unlocked is based on leaked data providing a detailed overview of hundreds of thousands of properties in Dubai and information about their ownership or usage, largely from 2020 and 2022.

The data was obtained by the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), a non-profit organization based in Washington, D.C., that researches international crime and conflict. It was then shared with Norwegian financial outlet E24 and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which coordinated an investigative project with dozens of media outlets from around the world.

The data includes the listed owner of each property, as well as other identifying information such as his or her date of birth, passport number, and nationality. In some cases the data captured renters instead of owners.

Journalists used the data as a starting point to explore the landscape of foreign property ownership in Dubai. They spent months verifying the identities of the people who appeared in the leaked data, as well as confirming their ownership status, using official records, open source research, and other leaked datasets.

The leaked property records show that other Afghan contractors implicated in alleged corruption schemes have also snapped up real estate in Dubai. They include Rashid Popal, whose private security firm was found by a 2010 congressional investigation to be using U.S. reconstruction funds to pay bribes to Taliban fighters and other militants, as well as government security forces controlling supply-route checkpoints.

Another former contractor, Saed Ismail Amiri, a California resident who was sentenced to 15 months in prison for his role in a scheme to defraud the government of Afghanistan out of more than $100 million, also owns a villa in The Meadows worth an estimated $1.6 million today, property records show. He did not respond to a request for comment.

And Stephen Orenstein, principal in the company Supreme Group, which along with subsidiaries, was hit with $434 million in fines and settlements by the U.S. government for overbilling the military mission in Afghanistan for food and water, owned a villa in the Emirates Hills community, which bills itself as “the Beverly Hills of Dubai” and features two golf clubs. The property last sold for $16.8 million in 2022. Orenstein said through a representative that he no longer owned the villa and that no money from U.S. contracts had been used to purchase the property.

The Meadows residential community in Dubai.

U.S. government auditors say billions of dollars in American reconstruction funds were stolen or misused over the two decades of Western intervention in the war-torn country.

The colossal scale of the theft “undermined faith in the international reconstruction effort” and diverted funds into “bribery, fraud, extortion and nepotism, as well as the empowerment of abusive warlords and their militias,” the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction noted in a 2016 report.

Much of that money quickly made its way to Dubai — a convenient three-hour flight from Kabul and with a glistening construction boom primed to absorb massive infusions of cash.

“We heard stories of people showing up with suitcases full of cash and purchasing blocks of apartments in the Emirates,” said Graeme Smith, a senior Afghanistan analyst with the International Crisis Group.

A Critical Year

By 2014, the optimism about foreign intervention in Afghanistan was fading fast, as the country was wracked by a strengthening Taliban insurgency. A disputed election that year put Afghanistan on the verge of another violent civil conflict, which was averted only by a power sharing agreement between competing presidential contenders.

That is also the period when the Rahmanis allegedly colluded with other families to artificially drive up the price of fuel on U.S.-funded contracts by more than $200 million, according to the U.S. sanctions notice. The father and son had also devised other tactics for driving up their profits, including underdelivering fuel supplies and fraudulently importing and selling tax-free fuel, the sanctions notice alleged.

In their lawsuit against the U.S. government, the Rahmanis said they “categorically deny any involvement in any fuel procurement corruption.”

“Our legal team is prepared and has substantial evidence proving that the referenced $200 million fuel corruption allegation is unfounded and not linked to us or any of our affiliated companies,” Ajmal Rahmani added in an email to reporters.

His father denied any involvement in the fuel business.

“I have neither held any fuel contracts nor conducted business of this nature with the US, NATO, nor any type of contract with Afghan governments,” Mir Rahmani wrote in a separate email.

Also in 2014, Ajmal Rahmani became a citizen of Cyprus, acquiring a passport through the European Union country’s citizenship for investment program after paying 2.5 million euros for a villa there.

That same year, Ocean Estate Company Ltd. — a UAE-registered company owned by Ajmal Rahmani — began developing an apartment complex on a plot of land in Dubai, which records show was purchased for $2.9 million in June 2013. The nine-story Ocean Residencia sits in Silicon Oasis, a planned community that advertises itself as “a global hub for business, a residential community and a specialized economic zone for Knowledge & Innovation.”

The land on which Ocean Residencia was built was sold to an unknown buyer earlier this year, after the U.S. sanctions were issued. However, rental contracts seen by OCCRP show that Ocean Estate Company Ltd. still owns the 110 individual units in the building, generating an estimated annual rental income of $1.3 million.

The company also owns sixteen residential units in another apartment complex, the Axis Residences. And through another Emirati company, The Fern Limited, Ajmal Rahmani owns the Fern Heights building, which contains 118 units, a number of which have also been rented out, earning an estimated $800,000 annually.

Ajmal Rahmani.

The land for the project was purchased in December 2016 for $4.04 million, and construction on the building began in 2018 –– the same year both father and son were campaigning in Afghan parliamentary elections.

Mir Rahmani had first been elected to parliament in 2010. On his website, he says he fought with forces opposing the Taliban from 1996, and helped U.S. forces invade Afghanistan in 2001. Before getting into politics, his son had sold bulletproof vehicles in Kabul, Reuters reported. On his website, Ajmal Rahmani says he had also been in the fuel business and “ventured into the real estate market in the UAE, starting with small acquisitions and building up his portfolio.”

‘Sudden’ Millionaires and Billionaires

The father and son both claimed parliamentary seats in 2019 following the 2018 vote, which was plagued by multiple delays and widespread allegations of fraud.

In its sanctions notice, the Treasury Department alleges that Ajmal Rahmani paid $1.6 million to members of the Afghan election commission to inflate his results “by thousands of votes,” and that Mir Rahman Rahmani “paid millions of dollars” to fellow politicians to buy his way into the speakership. From there, they allegedly used their official positions to further manipulate government contracts.

In a lawsuit they filed against the U.S. government on January 31, both men say they won their elections fairly and accused the Treasury Department of making “unsubstantiated, broad allegations” against them, which were “false and inadequate as a matter of law” and should be overturned.

But Judge Rudolph Contreras of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia struck down large parts of the Rahmanis’ complaint on April 19, including efforts to lift the sanctions pending the outcome of the lawsuit. The judge rejected their request to put an immediate freeze on the sanctions and rejected numerous challenges to Treasury’s authorities.

Yet in a response to a request for comment, Ajmal Rahmani said that the court had “issued a decisive ruling in our favour,” adding that they planned to challenge the aspects of the case that were dismissed.

Experts say Afghan elites were engaged in endemic corruption as private contractors responsible for everything from building schools to protecting convoys.

Between the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and the withdrawal of troops in 2021, Washington spent about $141 billion on efforts to stabilize and rebuild the country, according to the Government Accountability Office, which reports to Congress on federal spending.

The sheer volume of money being pumped into the country, paired with the challenges of vetting contractors and subcontractors, created a system that was ripe for exploitation.

“In the past 20 years, Afghanistan has seen the sudden emergence of millionaires and billionaires,” said an Afghan anti-corruption expert, who lives in Afghanistan and asked not to be named due to fears for her security.

“Those who were awarded contracts were often parliamentarians, ministers, or individuals closely associated with high-ranking government officials including the parliamentarians, ministers, vice presidents, or the president,” she added.

Vicious Cycle of Compromise

Among these well-connected Afghans was Rashid Popal, whose cousin, Hamid Karzai, served as president from 2002 to 2014.

Popal co-owned Watan Risk Management, a powerful Afghan firm described in a 2010 U.S. congressional report as “the principal private security provider and broker for the American supply chain in Afghanistan.”

The report, “Warlord, Inc.,” examined $2.2 billion in contracts paid to trucking and security firms tasked with transporting supplies to American troops throughout the country, often in remote or dangerous areas. It found that contractors, including Watan Risk Management, were using U.S. taxpayer dollars to regularly pay off Taliban commanders and other militants, as well as government security forces, in return for safe passage of the convoys they were guarding.

It was a vicious cycle — paying off the Taliban in order to supply troops fighting the Taliban — that made corruption and compromise inevitable for security firms like Watan, according to the “Warlord, Inc.” investigation, whose findings painted a damning portrait of how U.S. supply efforts were structured.

“What we were saying wasn’t that these guys were doing something wrong,” said Scott Lindsay, a lawyer who served as chief counsel to the investigation. “We were saying that the whole fucking design was fundamentally flawed.”

Popal denied congressional investigators’ assertions that he was paying off the Taliban.

Leaked property data show that a year after the publication of Warlord, Inc., Popal bought an office in the high-end Jumeirah Bay Tower. He also currently owns a villa in the Jumeirah Golf Estates. Although data doesn’t indicate when he purchased it, comparable villas have sold for the equivalent of $3.8 million in the past six months.

Popal did not respond to emails sent to two addresses that appear on documents related to his companies.

Destination Dubai

Afghanistan experts say they are not surprised that contractors profiteering from 20 years of U.S. funding chose to purchase properties in Dubai.

In 2022, Dubai’s luxury residential property market ranked fourth globally, behind only Los Angeles, New York and London, according to Knight Frank, an international property consulting group.

Palm Jumeirah archipelago in Dubai.

That same year, the UAE was added to a “gray list” by the Financial Action Task Force, an intergovernmental anti-money laundering watchdog. (It was removed from the list this year after the task force found it had improved its anti-money laundering measures.)

“Dubai became a kind of back office for the licit and illicit side of the war,” said Smith of the International Crisis Group, adding that rumors abounded in Kabul of money pouring into the UAE.

John Tierney, a former Democratic congressman from Massachusetts who played a key role in the “Warlord, Inc.” investigation, said congressional hearings revealed a significant flow of cash out of Afghanistan and into Dubai.

“There was one incident where they just basically had pallets with cash stacked on it and wrapped in cellophane,” said Tierney, who now heads the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation in Washington. “They put it on planes and zipped it out.”